For nearly 200 years the house on Captain’s Row in Sag Harbor has stood quietly aloof from the rest of the town. In a village of white clapboard, the dignified L’Hommedieu House is a red brick townhouse.

It was built in 1840, in the then-still fashionable Greek Revival style by Samuel L’Hommedieu (1785-1862), scion of a prominent local family. Every feature of the three-bay house is quiet, simple and restrained, with perfect proportions. The entrance features a wooden door surround with a pair of fluted Doric columns screening the sidelights, and the roof is almost flat–or as flat as they could make it in 1840.

But why brick? Why build a house that looks like it was scooped out of New York City and put down in Sag Harbor? A local story has it that L’Hommedieu built a Greenwich Village-style townhouse to entice his wife to live in Sag Harbor. More prosaically (and probably the truth) is that L’Hommedieu expected Sag Harbor, then a busy, wealthy port town, to become a city as important as New York. He himself invested in the whaling trade–he’s listed as the owner of the whaleship Henry in 1845, and the family business was a ropewalk on Glover Street. L’Hommedieu wasn’t to know that the whaling industry was going to decline rapidly in just 10 years.

L’Hommedieu was the grandson of a Huguenot fugitive named Benjamin L’Hommedieu, born in 1657 in La Rochelle, France. Benjamin landed in America at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1686 and then proceeded to dwell in a spot about 20 miles from New York City, which they called New Rochelle. Then they decided to go to Long Island, arriving in Southold around 1690. In 1694, Benjamin married Patience, daughter of Nathaniel Sylvester of Shelter Island. The L’Hommedieu family intermarried with many of the regions prominent families, including the Gardiners, the Nicolls and Mulfords.

The L’Hommedieu family particularly distinguished itself during the American Revolution, with numerous men serving in regiments and fighting in the Battle of Long Island. Captain Ephraim L’Hommedieu, for example, served as a Long Island Regiment Minute Man; he’s buried in the Old Burying Ground above the Old Whalers’ Church.

The most well known member of the family was Ezra L’Hommedieu. Ezra, the uncle of Samuel, was a lawyer who was born in Southold. He went to Yale, but, as a fervent patriot, moved back to Long Island when Connecticut fell under British control.

He was appointed by the New York Assembly as the state representative to the Continental Congress, serving from 1779-1783 and in 1788. He became active in provincial and state politics, serving in the State Assembly and in the state senate. He also was clerk of Suffolk County from 1784 to 1811, and a candidate to be one of New York’s first two United States senators in 1789, but lost by several votes.

Ezra, as a member of the New York City Chamber of Commerce, pushed to have a lighthouse built on Montauk Point. After all, he told President Washington, New York was the busiest trading port in the United States, and winds in winter meant that the city needed a lighthouse to aid ships sailing for the harbor. Ezra chose the site for the lighthouse and designed it. Constructed in 1796, Montauk Lighthouse was the first built in New York State and the first public works project of the new United States.

Apparently tireless, Ezra also worked on methods of improving farming, including using seashells as fertilizer, and corresponded with Thomas Jefferson about scientific farming.

Ezra’s first wife, with whom he did not have children, was Charity Floyd, sister of Declaration signer William Floyd. Ezra remarried after Charity’s death and had children with his second wife. He is buried in Southold with Charity.

Samuel’s father, known around Sag Harbor as “Old Squire L’Hommedieu,” was a justice of the peace. When “some roguish person or persons” threw the town stocks into a swamp on Gull Island, Esq. L’Hommedieu, “to vindicate the outraged majesty of the Law, offered a reward for evidence to convict the offenders. But who they were remains to this day a secret undivulged.” That is from Early Sag-Harbor: An Address Delivered Before the Sag-Harbor Historical Society by Henry Hedges, 1896.

Squire L’Hommedieu operated a ropewalk on Peter’s Green, just off Glover Street. A ropewalk is a long narrow building (1000 feet long) where workers walk back and forth twisting hemp into rope for use in ship’s riggings, line and cables. A busy port like Sag Harbor had an insatiable need for rope: a three-masted whaleship could involve six miles of rigging alone.

The old squire’s son, Samuel Junior, who built the brick house, was a member of the New York State Assembly for a time. Samuel married twice, and he and wives Mary and Maria are all buried next to one another in Oakland Cemetery, Sag Harbor.

Just a year or two after his death, the brick house became notorious among the community. The Civil War was raging, and by 1863 it was becoming difficult to recruit soldiers to the Army, even though many towns paid premiums to enlistees. East Hampton offered $400 to each man who volunteered, plus $3 per month to his wife and $1 for each child. But it wasn’t enough and the government began a draft. People in Sag Harbor heard of the famous draft riots of New York City and began to worry. Brothers Oliver and Jared Wade, who now lived in L’Hommedieu House, became aware of threats made to African-American residents of Eastville. Oliver distributed rifles among the residents and then was himself threatened. A mob formed outside the brick house. In return, Oliver armed himself with harpoon guns fitted with iron slugs: four guns pointed in each direction from the house. Fortunately, after a week or so, the furor died down and no fighting happened.

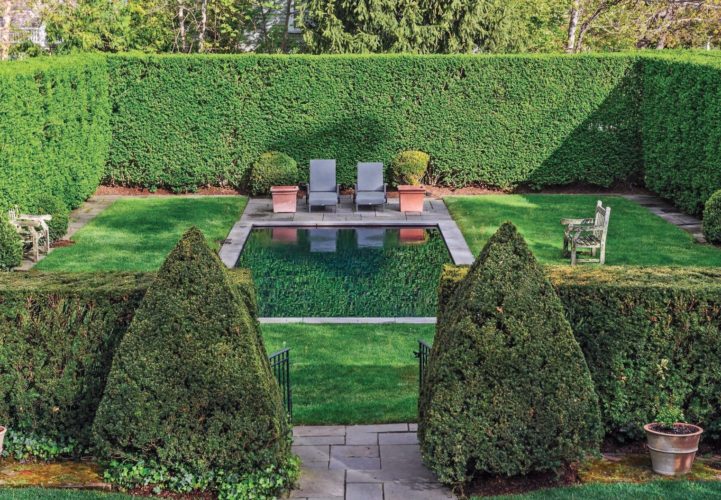

The old brick house continued for many years as a well-loved village landmark. In 2016 plans were drawn up to modify and renovate the house, including digging the cellar floor lower to create new bedrooms with ensuite bathrooms below ground, and, most controversially, altering the flat roof to create taller ceilings in the attic. These plans created outrage among Sag Harbor residents. After all, as it is, L’Hommedieu House is 5,000 square feet, with five bedrooms and three and a half baths. Why did anyone need more space, residents demanded.

But all is well. The house, with a fresh new beautiful interior but without the structural changes, was put on the market, and is at press time in contract to be sold. L’Hommedieu House should be greeting visitors to Captain’s Row for another 200 years, just as Samuel left it.