On the East End, horses aren’t just part of daily life — they’re a symbol of power and tradition, celebrated at the end of each summer for the last half-century at the Hampton Classic.

Franco Cuttica captures their spirit by building life-sized horses made of wood he forages along Long Island’s shores and on the forest floors, assembling them piece by piece, letting the natural shape of the material be his guide.

“Essentially the horse is in pieces on the ground,” Cuttica says of his process sussing out the wood in nature and then assembling it into this lifesize, hollow work of art that he sells directly and through galleries for five figures.

He insists, “All the form is there already. I just kind of put it together like a puzzle,” he says. “It’s almost like spilling a puzzle you’re about to do — and it’s all over the table. It’s kind of the same, but it’s all over nature and I have to find it.”

For Cuttica, it’s as if the horse sculpture is already predetermined, but, “It’s all by chance that it comes together by nature.”

“Whenever I’m driving, I’m always looking around on the roads at the beach, mainly bay beaches where I can drive off to the beach and there aren’t too many people,” he says. “All the wood that’s good on the beach I’ll snag because it has a driftwood look. But sometimes I’ll go up into the woods and find some stuff that’s like, you know, the root pieces from trees that fall over.”

Space to Build and Dream Big

Finding the wood is a fundamental portion of the job, but it is only the beginning of this artist’s journey. Then comes the preparation, drafting, modeling and assembling. Figuring out where each piece must go is like a jigsaw puzzle to which he only discovers the answer as he goes.

The building process takes place on Campo Cuttica, his family’s compound, tucked away on 40 acres in Flanders, the site of a former duck farm, now part-nature preserve, part artist’s haven. The former owner, late metal sculptor Gloria Kisch, developed the property and built a funky residence overlooking the lake.

“When we saw this, we were like, God almost made this for us,” he recalls of his family’s reaction. They purchased it in 2019.

The various artists in his family can both live and work surrounded by nature, utilizing old barns and other structures to experiment, craft, showcase and even store work. His father, Eugenio Aldo Cuttica is a noted painter from Buenos Aires, who intends on creating an artist-in-residency program under his tutelage. His older brother, Lautaro, and his wife, Isadora Capraro, are abstract artists and have studios there too.

Open any door to reveal all kinds of art from the Cutticas, many of them large canvas works that demand the space where they are stored. They also bring in different artists’ work from around the world to display.

“We’re trying to make this into a nice sculpture property, kind of like LongHouse,” in East Hampton, Cuttica says.

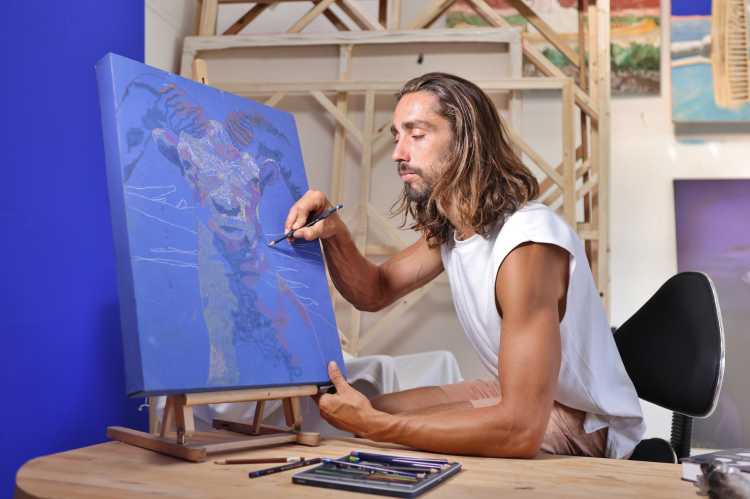

“I’ve always been kind of a builder, I would say. I’m surrounded by real painters, serious painters,” he says, though he enjoys painting and he’s quite good at it. “I do like realistic, almost photography-like realism. I can do that stuff, but I just don’t like sitting in one place. I like to be outside running around and throwing stuff around, and then go out to the beach, get more stuff.”

Speaking in his studio last summer, Cuttica described a live performance piece he does where he burns canvas with a torch, while Axel Quincke, a master concert pianist and friend in from Argentina, does more than tickle the ivories on a baby grand in the former duck barn a few yards away.

“We do a thing where he plays concert piano and I do a live fire painting,” Cuttica says. “And it’s like a nice little hour, 40-minute show. Usually, I’ll do a portrait. This is my go-to, Natalie Portman,” he says as he points to a large piece in progress.

No More Horsing Around

His family’s unique property is a long way from Argentina. In 1996, when Cuttica was just 6, his family emigrated to the United States, selling everything to escape political turmoil. He grew up in Brooklyn and attended various schools in New York City before moving to East Hampton to attend the Ross School. Though he appreciates his city upbringing, one that made him tough and capable, he credits Ross with developing his passion. The school fostered a contemporary approach to art, nurturing his talent and developing his love of nature. He graduated in 2008.

He began making the horse sculptures early on in high school. He doesn’t take credit for the original idea, though. “We [had] lived in Dumbo, right by the river,” when it was a true artist community, before its major redevelopment. “There would be a lot of driftwood that would wash up, and (my brother) and I would collect wood and bring it back to my dad’s studio because I would always build, like little boxes and little figures and cool little animals out of driftwood back then.”

His brother wanted to build a lifesize horse — probably the size of a colt — as a gesture for a girlfriend who had gone off to Europe for the summer, and he helped build it. “It was nothing like what they are now,” he says with a laugh. “It looked like a big raccoon or something.”

He helped prevent it from going up in flames when his brother’s relationship ended before the gift was delivered. This was their first summer in East Hampton, so they put it out in the front yard on Newtown Lane. It wasn’t long before someone made an offer to buy it.

They seized the opportunity and built another, and then another. His brother went off to college and he continued making them. Once he reached his senior year, he began taking it more seriously. He loved doing it, though he soon realized other artists made similar horse sculptures out of driftwood.

“A lot of people think I’m influenced by Deborah Butterfield,” he says of the American sculptor who has been making lifesize depictions of horses from found objects and natural materials, such as wood and recycled metal, since the 1970s.

If anything, it was the influence of Cuttica’s father, who taught him everything he knows, he says. His father helped give him direction in those early years “because he’s very good at making sculpture in three dimensions,” Cuttica says. “He has a very illustrative, genius brain. So he would help me make the aesthetic decisions, and I would take care of most of the building production.”

By his senior year, around the time when the 2008 recession hit, it became a family affair as his father recognized, ‘There’s something to this horsemaking business,” he remembers. “We made tons of horses that summer, and we survived as a family selling horses during the recession.”

Crafting the Collection

Some 17 years later, through stints at Pratt Institute and Cooper Union to study architecture, Cuttica has continued to hone the craft. He estimates he’s made more than 300 driftwood horse sculptures now, and the process, like the work itself, has evolved over two decades.

“I used to go out there and get all the pieces possible and just like collect, collect, collect, and have like a mountain of wood almost — you couldn’t even see the grass, there’d be so much driftwood everywhere,” he recalls.

But that process wasn’t working for him; he found no artistic flow in the heap. “Things didn’t really relate to each other because I would use a fence post and then a curvy piece and then whatever, just to cover the horse — to make a basic form,” he says.

“Now I really let the wood dictate the building,” he says, noting that he has developed a routine process, similar to opening a box with a new piece of furniture accompanied by step-by-step instructions to assemble it.

“You start with the legs, you put them on. There’s like a structure inside the body that I also developed. It’s almost like a very narrow bar table and you slap the legs onto that and so then it’s all unified and strong. Then there comes the belly piece, which is a long kind of view, which is the only part of the horse that has that, and then the back, which is a long ‘S’ — it kind of dips. And then the butt, you know, the back and the butt … that’s its own form.”

But first, he draws the form of the horse utilizing those shapes. For instance, the barrel of the horse, or the belly, is long ‘U,’ he says. “Each part of the horse has its very specific type of shape that sometimes nature makes, sometimes it doesn’t. So I have to go out there and really look to find the right pieces. Now I’m only picking up like 5% of what I see out there,” he says.

“I’ve honed the process where it’s less of me imposing onto the form and to where it’ll be determined,” he adds.

It is a painstaking process that takes about a month to complete from start to finish, so he averages around 10 per year. He can spend up to a week just cutting, using big saws, then working with sanders and planers, where he takes wood off the surface. He has to hold pieces of wood up, then screw them down. “It’s like a challenging workout, both physically and mentally.”

The expression of the horse, how it carries its head, is also dictated by the wood. “The more I force it, the more I want it to be something, the more where the horse doesn’t look natural,” he notes.

No two horses ever look exactly the same. “That’s kind of why I can keep doing it because every horse comes out different — and then I’m excited about it because they’re all unique in their own way.”

He doesn’t name them. “It’s not me making them, it’s nature making them. So I almost can’t name them,” he says.

Standing in Power

It’s all worth it to see the finished product, which he feels captures the horse in a moment in time. He calls it “a very static position — standing and strong, but almost about to move,” as he points to one of the pieces, the horse’s head ever so slightly tucked downward. “It has that look of readiness, but also fluidity to it. Fluidity, but also it feels like it’s standing with stability — in its power.”

While he does not force the wood into any position, he does mold it, such as sanding to bring out a different texture — “a kind of balance between the perforation of how much air can go through, visually and structurally.”

“I usually like to work life-size or bigger. The smaller I go, the more the wood cracks and can’t really handle the stresses. The bigger I go, the more I feel a connection as far as scale. Maybe because I’m a tall guy and, you know, kind of big hands — I just hate working with like little pieces.”

The sculptures can be placed both indoors and out. “Most people who buy them don’t have room indoors, so they just put them outside. I treat them and prepare them as much as possible for outdoor use,” but like a wooden outdoor chair or table, it’s only going to last so long.

He uses a Japanese technique to burn the inside of the sculpture to prevent rot from bugs and moisture. “By burning it, preserves it,” he explains.

He has dabbled in other sculptures, such as an elk that he was commissioned to do. “It was almost easier. The horse has so much volume. You’re trying to replicate this big butt, chest, big neck, and it’s almost like the wood has to be extra curvy to fill out those spaces. But the deer is just, a nice, slender form and super easy to make in terms of volume — very skinny, very compact.”

For someone who has become so intimately familiar with a horse’s body and how it moves, it may surprise some to know that he’s not exactly an equestrian (though he’s ridden in Argentina). That might be at the root of why he keeps creating these sculptures in their images.

“That’s kind of part of, I think, why I make them, to have a connection with the horse and the spirit,” he says. “One day, I’ll definitely have some horses.”

That’s the dream — to have a horse farm, not just a stable full of his horse sculptures.

“Many people don’t think about it much, but the horse is very integral part of the process of our contemporary age. It’s a symbol of strength, of movement — of all kinds of things — freedom, a symbol of development, a symbol of making a large area seem more accessible. It’s a symbol of strength and evolution, the horse. And buying a horse or having a horse around can kind of bring that kind of energy and that spirit into one’s home,” he says. “I think that’s why people buy them.”

This article appeared in the Labor Day weekend issue of Behind The Hedges in Dan’s Papers. Tap this link to read the full digital version. For more Master Craftsman columns, click here.