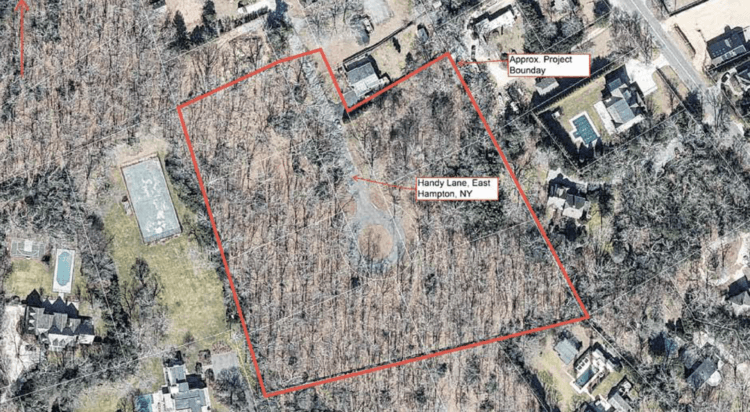

For years, Handy Lane was a sleepy little Amagansett street with modest homes that dead ended into a densely wooded, 2.11-acre area.

That all changed with the East Hampton Planning Board’s 2015 approval of Salty Development’s plans, paving the way for an eight-parcel Handy Lane Development subdivision with homes starting at 3,847 square feet and going up to 7,081 square feet on parcels ranging from 0.29 to 0.83 acres.

To date, six of the homes have been built and two are in contract, including 36 Handy Lane, which has yet to be completed.

Amagansett Neighbors Protest Development

The subdivision has incensed several neighbors, including Harold Koplewicz, who started a #SaveAmagansett petition warning residents of overdevelopment, the encroachment of out-of-place McMansions and the destruction of environmentally sensitive wooded areas. To date, the petition has garnered 73 signatures.

Residing on Skimhampton Road which abuts Handy Lane to the south, Koplewicz, who has summered in the Hamptons for four decades, notes property owners are subject to all manner of building restrictions, but not Salty Development, which accomplished the zone change under the banner of urban renewal.

By building the development in two separate phases, the developers were able to circumvent environmental review, cut down trees at a time of year which impacted the mating Northern Longeared Bat, an integral part of the local ecosystem, and take away rare plants, whose removal would have otherwise been prohibited by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Due to the idiosyncrasies of zoning regulations, smaller pieces of property, like those in the Handy Lane development, are permitted a greater percentage of lot coverage than 2-acre parcels.

“One of the neighbors now will have four or five swimming pools directly on his property line,” says Koplewicz.

Along with two other residents of Skimhampton Road, including architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Koplewicz hired attorney Tiffany Frigenti to see what legal remedies could be effected. The first phase called for dividing the land on the west side of the cul-de-sac into four separate parcels. When neighbors objected to this phase, the planning board required a conservation easement which prohibits cutting down trees on that side, explains Frigenti, of Lynn Gartner Dunne of Mineola.

Phase two, on the east side, was approved under an urban renewal clause, which didn’t require a conservation easement or serving surrounding property owners notice, meaning it could easily fly under the radar, says Frigenti.

“Technically, they had the authority to use the power, but I think the way they used it is in contravention to the very purpose of what urban renewal is for, which is to stop overdevelopment and all these other environmental issues that this development has exacerbated,” Frigenti says.

On June 10, 2022, Frigenti wrote to the East Hampton Town planning board and building department requesting they rescind their March 12, 2015 decision permitting the subdivision, rescind building and pool permits to all eight homes in development and issue a stop-work order to restore the conservation easement area and revegetate the over-cleared lots.

Since the zone changes and permissions were granted in 2015, from a legal perspective, the neighbors’ complaint, which also includes segmentation of the environmental review, is past the statute of limitations, which would be at most one year after the board’s determination.

Though it’s too late to truly rectify the situation other than to revegetate the over-cleared land, Frigenti hopes the town will stop developing the two remaining lots until a proper assessment of the environmental impact is completed.

Aware of the pending legal status, Koplewicz still questions whether a half-acre parcel with a 4,000-squarefoot home, pool and pool house is actually good for the environment.

“Is this really good for the Hamptons?” he adds.

Saving Trees — in the Future

If the developers have over-cleared the land or encroached on the conservation easement, they’ll be required by the town to have a revegetation plan, notes East Hampton Town Councilwoman Sylvia Overby, a liaison to the planning board, which she formerly chaired.

“It’s got to be something that’s submitted, and we can see it, and the public can see it, and we know what you’re putting in there,” says Overby.

As a direct consequence of the Handy Lane Development, this summer the Town Board passed legislation clarifying that a “developer has to stake the property where clearing edges are so they can’t say, ‘We didn’t know it was there,’” says Overby, adding that it has to be clearly marked on the survey, as well as on the property itself, either via staking or fencing.

The new regulations will prevent a situation like Handy Lane from happening again — elsewhere in the town — because, Overby says, “You can’t replace a 50-year-old tree.”

To further deter developers from clearing properties, the town also recently increased fees for revegetation plans, which are required before they get their certificates of occupancy, notes Overby.

The town board, Overby predicts, will consider adding greater restrictions to land clearing on smaller properties and might take a look, as the previous administration did several years ago, at restricting the size of newly constructed homes.

“I think there’s interest in looking at that,” says Overby, adding that builders and real estate agents will undoubtedly express contrary views on the matter.

For now, residents of Handy Lane and Skimhampton Road must contend with a boundary line of trees where there was once a heavily wooded area, which Frigenti argues contradicts the town’s efforts to conserve open space.

Over the years, Koplewicz has been irked by the many town regulations, like requiring residents to get a beach sticker each year, but notes, “At the end of the day, it saves the environment. We don’t have too many cars at the beach.”

Sympathetic to neighbors’ concerns, Overby, who lives in Amagansett, and calls herself a “tree person,” says, “I want to make sure that our woods and woodlands stay as much intact as possible. Otherwise we do become like any place and that’s not the direction East Hampton wants to take.”

Having lived on Skimhampton Road his whole life, Adam Abelson, who is the third litigant in this matter, questions why this developer was able to take advantage of loopholes in the stringent building code while everyone else must abide by them.

Though he’s aware this development can’t be stopped, Abelson hopes nothing like this happens again.

“The goal, if the horse has left the barn and this is a fait accompli, hopefully, is if they continue to overdevelop, these loopholes are addressed in a transparent manner that includes the voices of the people who live here, pay taxes, and are really the true representatives of our community,” Abelson says.