It’s a rare and beautiful thing to encounter someone on the cusp of greatness, or great things to come. And so it is with artisan woodworker and Greenport native Ricky Saetta, if he decides to go that route. Opportunity has knocked and he stands poised at the other side of the door.

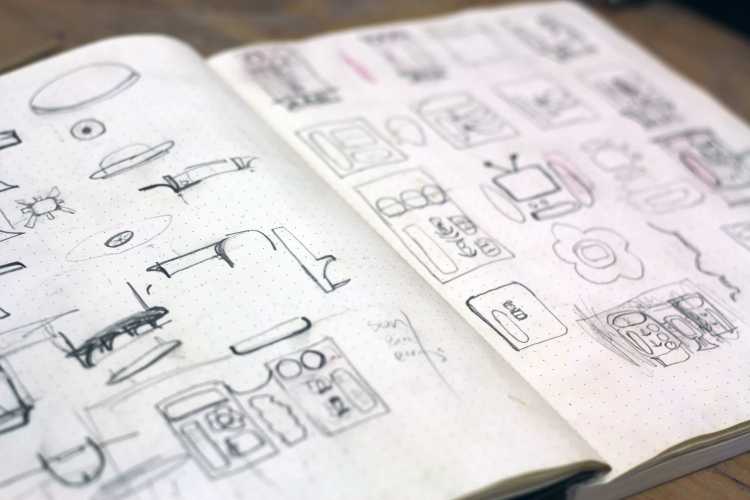

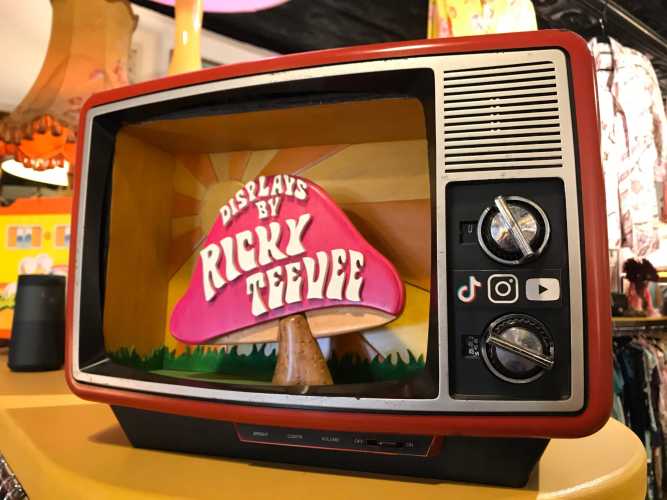

A carpenter and wood finisher by trade, 40-year-old Saetta has entered a new phase of his career, designing and fabricating a range of custom wood store displays, signs, furnishings and much more. Functional and decorative, Saetta’s creations often feature integrated video elements, which he produces by editing together clips culled from dozens of hours of vintage footage found via YouTube and other sources, to be played in a loop on stylishly outdated picture-tube televisions.

This unusual mastery of such diverging skill sets — a knack for building in the physical and virtual spaces — has brought Saetta a great deal of attention through his installations at local businesses and a well-curated collection of photographs and video on social media platforms such as TikTok and his popular @ricky.teevee Instagram account, which has more than 9,000 followers.

His reputation is growing on the North Fork as more people encounter Saetta’s one-of-a-kind builds at the Lucharitos restaurants in Greenport, Mattituck, Aquebogue and Center Moriches, White Flower Farmhouse in Southold, and The Times Vintage shop in Greenport, where he continues to expand his artistic footprint in a decidedly retro style.

The latter project, in fact, is so inspired, it caught the attention of Larissa Blintz, owner of Miracle Eye, a Los Angeles-based vintage clothing company. Blintz saw Saetta’s designs for The Times Vintage on Instagram and hired him to create similar storefront displays and furniture, especially the “space-age vanity,” for her business. “She was like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to have that,’” Saetta explained while putting the finishing touches on his Miracle Eye pieces before hitting the road and hauling them to L.A.

Saetta’s work kept him plenty busy before committing to the Miracle Eye project, but he admits that taking his vision across the country marks a major milestone in his trajectory as a craftsman. “It’s going to be a wild trip,” he said just days before leaving. “She called me three months ago, and I was like, ‘Let’s do it.’”

The woodworker was born into his chosen profession. His father, Bob Saetta, is also a talented carpenter who rebuilt Orient’s Long Beach Bar Lighthouse, best known as the “Bug Light,” in 1990, 27 years after it burnt down in a 1963 fire. “My dad’s done a bunch of stuff out here and he’s super creative, I learned the trade from him,” Saetta says, noting that he spent his formative years in construction, but eventually began traveling, first to New York City and then points west.

He earned his stripes as a finish carpenter in San Francisco and Phoenix, but the East End called him back home. Saetta worked a bit more for other companies in the area, but then everything changed.

“When I got back here, I was working for North Fork Woodworks for a couple years, but in 2015 I had a daughter with someone from Southold,” he says. “When my daughter was born, I made her crib, and I started making a name sign for her, and then I started making some name signs for my friends’ kids, and I just started sliding more into the creative element of woodworking and whatnot,” Saetta says, recalling his path to what he does now.

By 2018, he’d split from his daughter’s mother and had grown weary of working as a carpenter. The day job took time away from his growing number of side projects, so he quit his job and set out on his own to see if he could turn that side work into a full-time business. “It was very rough in the beginning,” he says. “I was doing a bunch of different things and trying everything out.”

During this period, Saetta made a series of retro cassette tapes out of driftwood and an array of other materials. He tried to sell them, but quickly realized sales is not his forte. He is the first to admit that money and business-related matters are well outside his wheelhouse, though he promotes himself masterfully online.

“I don’t have that motivation for income,” he explains. “I don’t have that drive. … I get bored in the process. I don’t want to respond to emails. I don’t want to do any of that. I hate that shit. I just want to work.”

Saetta has never struggled with putting the maximum effort and hours into his creations, but that drive to make things as amazing as possible often hurts his bottom line. He regularly puts in man-hours well beyond what he’s being paid. But he wants each project to represent his very best.

“A lot of the jobs I’ve taken since I went on my own, I didn’t care so much about money — I wanted to show off,” Saetta says. “I wanted to really challenge myself and do the work I knew I could. A lot of the times I’m not being paid well at all in the beginning because I’m intentionally putting everything into it and I don’t care.”

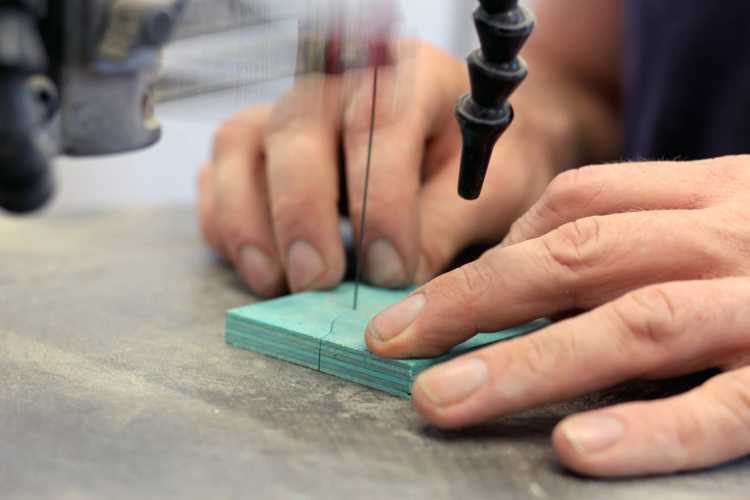

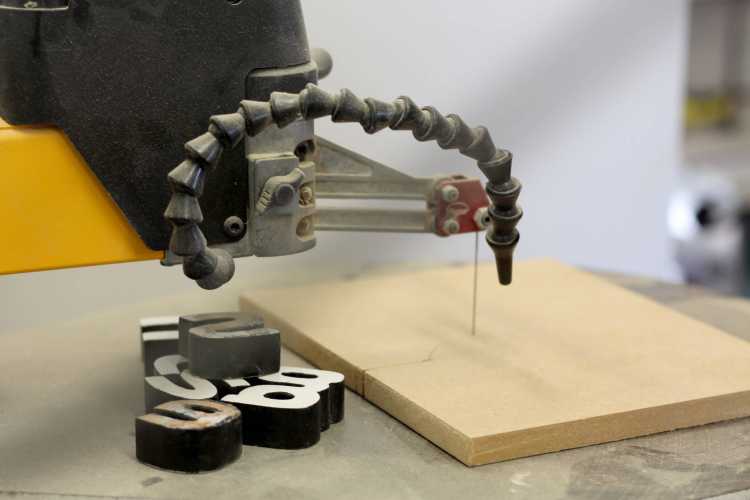

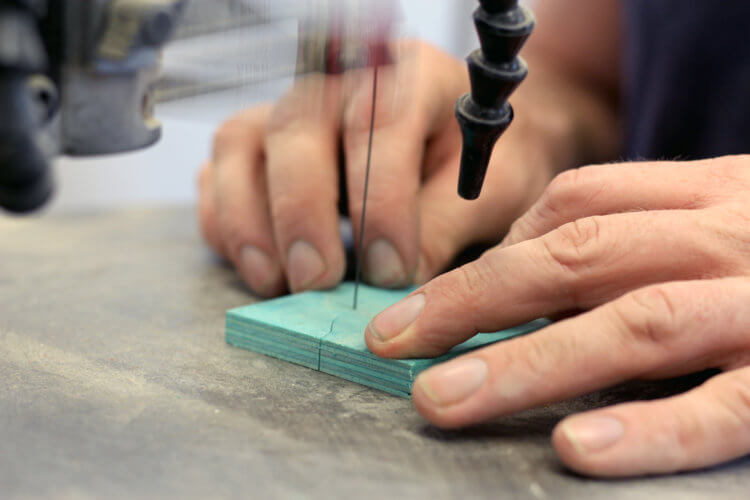

He shares, for example, how he made 550 hand-cut flowers on his scroll saw in order to form three-dimensional vintage-style wallpaper in one of The Times Vintage dressing rooms, and he cut 100 butterflies for the other. “The time I spent on this was asinine and she couldn’t pay me for it, really,” he says of the store’s owner Elizabeth Sweigart, who later became his girlfriend.

“I’ll cut 500 flowers by hand if it’s going to look insane. I don’t care about how much I’m paid per hour, and that’s not good for me business-wise, Saetta continues, describing this approach as a sweat-equity investment into work that will invariably end up in the public eye. “When people hire me, they get more than they’re paying for. I care a lot.”

Saetta feels uneasy about calling himself an artist, but he’s also aware the descriptor fits well with what he does. He never likes making the same thing twice, no matter how many people ask for it, and he’s loath to get pigeonholed into a particular style. “I get a lot of requests and I kind of just take the ones that I find interesting. There is no order, really, and that’s annoying for a lot of people who reach out,” Saetta says. “I’m hard to get in touch with, I’m flaky, but then suddenly when I’m doing your project, I’m all the way up your ass and I’m working 14-hour days on your stuff. That part they love.”

This ethos, while certainly respectable, begs the question of whether or not Saetta’s exquisite aesthetic and exemplary work will be enough to carry him to the heights of success he’s so clearly positioned to achieve. “I feel inevitable. I feel that all the work I’m doing is going to be seen at some point and going to be recognized,” Saetta says, but as he stands listening to that plentiful future knocking, only he can choose to open the door.

This article appeared in the October 2021 issue of Behind The Hedges. Click here to read the magazine online.