Though he works in many mediums, Scott Bluedorn has spent large swaths of his artistic life exploring a single unifying theme.

Whether realized through painting, sculpture, collage, furniture design, printmaking or other art forms, Bluedorn’s work lives at the intersection of the natural world and the world of human beings.

“A lot of what I do centers around the idea of civilization meeting and clashing with the wilderness,” he says.

That ethos is particularly evident in Bluedorn’s work with found objects, which he refers to as “castoffs of our industrial civilization.”

For example, “Lost Sou(u)l(e)s” (2014) is a collage of well-weathered flip-flops, sneakers and water shoe fragments created with items gathered in and around the beaches of Montauk; Above the Island (2022) is a traditional nautical scene drawn with graphite pencil on a sliver of found plastic; “Trackgrid 1” (2011) is a meandering, yet entirely logical geometric pattern created from surfboard traction pads.

Bluedorn, 37, is a true child of the East End. He was born in Southampton and grew up in East Hampton Village, just a few blocks from the ocean.

In early August of this year, he opened a new studio on Butter Lane in Bridgehampton, which he shares with the digital artist Harris Allen. So it’s not surprising that life on the water is one of the primary engines that drive his work.

“Travel, particularly nautical travel, was always the world I was interested in,” he says. “It wasn’t so much the working waterfront. I don’t come from a fishing background. For me, it’s more about history, commerce and culture, all centered on shorelines and water. And that extends into the ocean itself and the natural world and how it represents a wilderness.”

“I think my work would be very different if I was born on, say, a farm in Iowa,” he continues. “But I probably would have eventually come to the water.

I started with the ocean as my obsession. But now it’s the entire natural world because it’s such an interconnected system — mountains, fields, forests, the ground underneath the earth, the sky…”

An avid surfer, Bluedorn also draws creative energy from the surfing world, particularly the sport’s roots in primitive island culture. The surf-related art he makes fits naturally into his wider vision.

“I don’t look at surfing in a pop culture way,” he says. “I’m more interested in how it connects to ‘timeless times.’”

“It’s elemental,” he adds. “There’s been progression within the sport itself, but essentially, it’s just you and the ocean.”

Exploring a New Medium

Bluedorn has recently added a new medium to his ever-widening portfolio. He has begun creating wallpaper — an artistic evolution that happened partially by accident.

In 2020, he was working on an installation for the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill. The Bonac Blind is a floating, off-grid “micro home” that references the traditional Springs/East Hampton Bonac culture of fishing, farming and hunting.

Bluedorn’s intent was to comment on the erosion of our culture in the face of the housing crisis, climate change and modernity. The structure is modeled after a functional duck blind covered in native grasses, but also includes a large geodesic dome window for observation. It was installed in an inlet of Accabonac Harbor in Springs, where it floated for six weeks before it was moved to the main grounds of the Parrish Museum.

Bluedorn created his first wallpaper fragment to adorn part of the interior of “The Bonac Blind.”

“I used a lot of my drawings over the years and made them into a “Bonac toile” pattern,” he explains. (Though it literally means “cloth” in French, the word toile in this context refers to a design aesthetic that gained popularity as a printed French fabric in the late-18th century.)

He has since begun designing new patterns derived from his drawings and paintings, which he sells online and at his new studio in Bridgehampton.

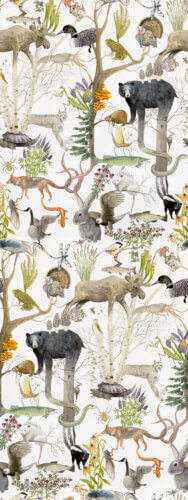

His latest wallpaper pattern, which he calls Interconnection, started as a watercolor painting. To describe the work’s aesthetic, Bluedorn quotes the naturalist and environmental philosopher, John Muir, who said, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

“I think that’s a really amazing metaphor for the natural world,” Bluedorn says. “One that our civilization needs to understand.”

“Visually, the wallpaper pattern is all these plants and animals being connected to each other,” he continues. “Whether it’s by arms, legs, antennae, plant roots or something else.”

Though wallpaper-making is a relatively new endeavor for him, Bluedorn was able to draw on his training and experience in printmaking and commercial art. However, the repeating patterns inherent in the wallpaper-creation process forced him to cultivate a few new design skills.

“It was like a puzzle trying to figure out how the left side was going to connect to the right side and the top was going to connect to the bottom,” he says. “That was a new thing for me. I had to teach myself how to do it — how to make sure the seams were lining up.”

Any attempt to deconstruct Scott Bluedorn’s art has to take into account the irony, the whimsy and the strong whiff of the surreal that inhabit his work. In fact, in his biographical materials, he describes himself as a creator of “surreal imagery inspired by maritime history, cultural anthropology, myth, supernatural themes and the natural world.”

Maybe Bluedorn’s ethos is best summed up by a work in progress he’s calling “The Macro Plastic Inventory.” Painted on YUPO, a synthetic paper made from polypropylene resin, a series of small images, each about the size of a large postcard, depict found objects that the artist has gathered from up and down the Eastern Seaboard. When seen from a distance, the fragments look more like random geometric shapes than man-made objects. But as viewers draw closer, they begin to identify the contours of a piece of construction fencing, a lobster tag, a clarinet reed, even a kitchen spatula.

Ultimately, Bluedorn plans to expand “The Macro Plastic Inventory,” which he refers to as “paintings of plastic on plastic in a plastic world,” to include objects from around the globe.

As long as he keeps making art, Bluedorn is likely to keep probing the way in which the world of humans clashes with the natural world. He doesn’t pretend to have the answers, but he fully intends to keep asking the questions.

“The natural world is a perfect system, whereas ours is not,” he says. “Civilization is a linear system that’s gonna end in catastrophe — or something else entirely.”

This article appeared in Behind The Hedges issue on September 1, 2023. Read the full digital edition here.

ceramic with copper base (2022)Courtesy of Scott Bluedorn