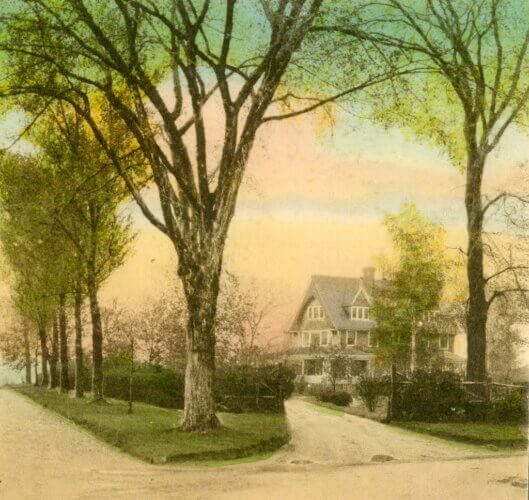

The Mayfield Estate, a Gothic Victorian home set along Southold Bay on the North Fork, has held an allure since the very time it was built.

The Southold property’s two-plus acres include 150 feet of private sandy beachfront, a six-bedroom, four-bath estate house, a small beach house and even a three-story high lighthouse. The 5,000-square-foot main house was even identified as historically important by the Society for the Preservation of Long Island for its contribution “to the ambiance of historic Town Harbor Lane.”

“While listed on SPLIA, the house is not landmarked and we truly hope that the next steward will be a caregiver who recognizes the importance of preserving the history of the house and maintaining it for the community’s benefit,” says Nicholas Planamento of Town & Country Real Estate, who has the exclusive listing on the home, now asking $5.999 million.

Completed in 1907, the bayfront abode was built by J. Edward Corey for Louise (Neuman) Ruebsamen and her young son – whose own story was a source of endless intrigue and speculation.

Lighting the Way for Rumrunners

According to In the Modern Era: Essays on 20th Century History, a book put out by the Southold Historical Society in 2015 to celebrate the town’s 375th anniversary, Neuman was born into a well-to-do New York City family who owned a lithography business. She married Robert Ruebsamen and had three sons before abandoning the family and giving birth to a fourth son in 1895.

She boarded with Dr. George S. Conant, a physician with many wealthy clients, in the city. When Conant died in 1904, Ruebsamen and her youngest son John inherited everything in his estate — much to the chagrin of his extended family, who challenged the veracity of the will and why he had been cremated hastily, though there was no evidence any suit was filed.

After spending several months in Europe, she returned to New York and set her sights on the North Fork, where she had spent summer vacations. Even back then, the area was marketed to summer visitors, many of them from Booklyn and Queens. “It was eventually so full of Brooklynites during the summers that it became known as the ‘Brooklyn colony,’” the book explains in a chapter written by Geoffrey K. Fleming.

She bought the property on Town Harbor Lane in October 1905, as the local newspaper reported, “The house will be a large and handsome one. Work will be commenced immediately. No finer location for a residence can be found on eastern Long Island,” according to the book.

The large, lavish house was unusual for the time, surrounded by fishing shacks and farmland, the book explains, describing its English Arts & Crafts feel, shingled exterior, steep roofs, diamond pane windows and large chimneys.

Though her son went on to open a real estate business in Southold, by the mid-1920s, Louise Ruebsamen was forced to sell her home due to dwindling funds.

Legend has it that the lighthouse was built by the next owners, Wilhelm Kaupe, a silk importer and a merchant who lived in Manhattan and later on Staten Island, and his second wife, Kathryn Kaupe, during Prohibition.

A lot of people were engaged in rumrunning on the East End, and the theory was that people bringing whiskey and other liquor to New York City via the North Fork would rely on the lighthouse beacons to find their way.

“You have to remember there weren’t so many houses. Navigational lights just didn’t really exist, the way you see things today,” Planamento says, adding, “These were typically wealthier people, that were involved in rumrunning.”

This house’s basement has a hole, four feet in diameter, in the brick wall which led to a room that was described as a bomb shelter.

But, Planamento has learned from history buffs around Southold, that the house had a tunnel between the basement and the bank at the bluff along the bay used for rumrunning.

“A boat would land offshore,” Planamento says. “You’d row a boat in and out, deliver the goods. They would take things from the beach via this tunnel into the house.”

Though it’s undocumented, Planamento says it does make sense that an owner in the 1950s Cold War era would have then utilized the basement and tunnel as a bomb shelter.

Pre-zoning Additions

In addition to a working lighthouse, Mayfield Estate has a beach house with a kitchenette and room for changing.

“That was built before zoning. You can’t do that today. So that’s a huge value,” says Planamento.

The house also has a third floor, which is no longer permitted under the current zoning regulations.

Everything was built prior to 1957 when the code changed, says Planamento, adding that because of the house’s historic deed, the homeowner actually also owns the underwater land.

The lighthouse is an actual working lighthouse, notes Paul May, whose parents, the late John and Elinor May, purchased the property in 1979 from Florence LaFreniere, after the death of her husband, Southold attorney Edward LaFreniere.

Their 11 children are now selling the home that they coined the Mayfield Estate, which their parents have preserved over the last four decades. It hit the market early last month.

“Over the years we have replaced the light fixture and timer and at one point installed a solar-activated light that is only on between sunset and sunrise,” May says of the lighthouse.

As for the main house, it remains as impressive as ever. There are a total of seven fireplaces, including in three of the bedrooms and a double-sided fireplace in the dining room/kitchen, front and back staircases, a den/sunroom, windows with diamond-patterned mullions in the kitchen and den, hardwood floors, a coffered ceiling in the foyer, a three-car garage with a heated and air-conditioned office, plus a two-car garage with a loft, a jacuzzi room on the first floor, and two bedrooms, bathroom and den on the third floor.

In addition to the sprawling front porch, there’s a porch off the kitchen, a waterside porch, plus a large deck, that was added on in the late 1980s.

The home is sited in a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Zone X, notes Planamento. “When you live in Zone X, which is high and dry grounds, and as good as you can get, you don’t need flood insurance and your risks of flooding due to a natural disaster are very slim, actually non-existent,” he explains.

Fun family memories

At the time his parents purchased the estate, they lived in Old Westbury and owned a summer house in Southold, Paul May remembers.

“They weren’t ready to buy a retirement house, but this house became available, and it was the perfect house,” says May,

The Mays rented out the house for about 10 years, after which they renovated it over a five-year period and then moved in.

Part of that renovation entailed incorporating a section of the wraparound porch into the bay-windowed living room so that it would be a perfect fit for Elinor May’s grand piano, says Peggy May, Paul’s wife.

“It fit right in there, so she could play and look out on the bay,” says Peggy May.

Christmas was always a truly special time at the house, recalls Paul May, where on Christmas morning everyone came down the stairs one by one to admire the magnificent tree in the living room. When they were finished opening presents, they would all head into the library where they’d find the dozens of stockings for parents, children and grandchildren hanging from the fireplace.

Though the house was always buzzing with family and friends, Paul May recalls the weddings on the lawn of four of his siblings and, in particular, his two daughters, as particularly memorable.

“The lighthouse, Moon and bay view made the weddings magical,” May recalls. “After dinner and dancing at one wedding we walked down to the beach for a bonfire and one or two people from the band came down and played acoustic guitar and we sang around the fire.”

This article appeared in Behind The Hedges issue on September 1, 2023. Read the full digital edition here. Be sure to check out more Real Estate Roundtables.