Like the rotation of the earth and sun, the orbit of our galaxy or even racing around an elliptical track, there’s something beautiful about that which ends up where it began, especially when one considers all the life lived and knowledge gained along the way. We’re invariably more prepared for our second lap, tomorrow or next year.

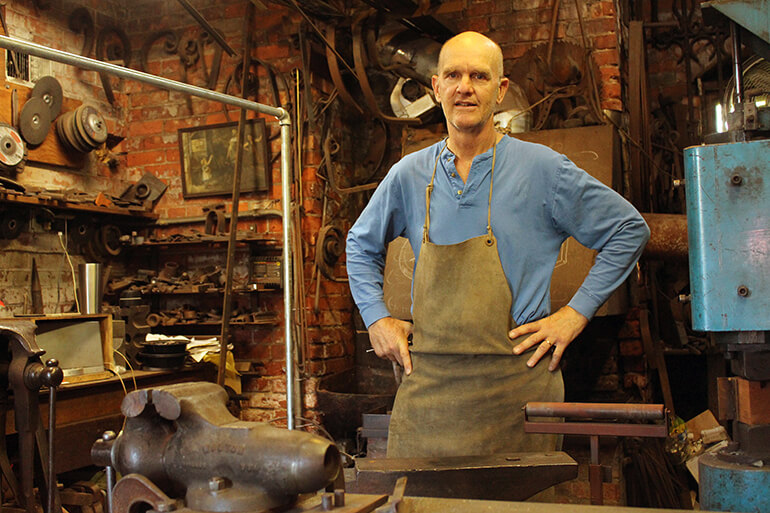

Sag Harbor blacksmith and metalworker John Battle has spent the last 50 years honing his craft, first along a path to becoming a metal sculptor, and then later as one of the East End’s most skilled and experienced men in his trade. Now, 34 years after opening his metal shop, Battle Iron & Bronze in Bridgehampton, and working on high visibility local projects, major commissions and thousands of smaller jobs, the artisan is returning to his art.

“It’s not a snap of the fingers to go back from being a craftsman to being an artist,” Battle says during a chat in his shop, surrounded by rusted metal artifacts, works in progress and hundreds of objects gleaned from a lifelong obsession with collecting–all housed within a historic ivy-covered brick building near the Bridgehampton LIRR station on Maple Lane. “I’m rediscovering things I took for granted,” he adds. “I don’t really know where I’m going.”

Battle does, however, recall keenly where he began. “I started with this when I was 12 and I’m 66 now, so you do the math,” he says, explaining his enduring passion for metalwork. “For some unknown reason I just gravitated toward metal and wanted to work with it.”

Early on, while growing up in Princeton, New Jersey, he enjoyed support from his artist mother and a willing teacher who spearheaded a successful effort to create a simple metal shop in the corner of his school’s art room. Hidden behind a protective curtain and using a primitive ventilation system, Battle had his first taste of welding and bending metal to his will. His path was set, even if he didn’t yet know it.

In high school, Battle further honed his skills and gained an appreciation for the East End at his family’s summer home in Sagaponack. He worked at Dave Halsey’s metal shop on Scuttle Hole Road, withstanding practical jokes regularly from legendary local character Count Strong, who also taught him invaluable techniques of the trade. But Battle believed he had a future in sculpture, not fabrication and repair.

“I wasn’t a craftsman,” he says, looking back at his time majoring in architecture and visual studies at Dartmouth College. Battle worked as a carpenter to earn money after graduating, eventually building a dinner theater and a restaurant in Boston, while still pursuing metal sculpture. “I worked six months as a carpenter and six months as a sculptor,” he says, reminiscing about his studio in an old South Boston school basement. “I’d build up a body of work, and in the fifth month I’d figure out how to put up a show.”

After mounting exhibitions at the studio and building a reputation locally, Battle landed his first one-man show with Helen Schlein Gallery. The respected dealer took to his found-object assemblages, each an atavistic, abstracted representation of something real–a style Battle continues to explore–and the work was reasonably well received. But youth and naiveté often get in the way of a good thing.

“I didn’t know how any of it worked…I wasn’t there,” Battle says, admitting that he moved to New York City believing he’d “conquered Boston” even before his first solo show opened at the gallery. He had one more show with Schlein the following year, but Battle was now getting requests for more traditional metalwork, and the artistic path slowly gave way to that of a dedicated tradesman.

From his very first major commission–creating a pair of decorative iron gates at NYC’s Hispanic Society of America museum–for which he was wholly unprepared, Battle’s talent and good luck helped him build a thriving business, though it took time for him to fully commit. After moving to the Hamptons year round in 1985, he taught at the Hampton Day School and did metalwork on the side for seven years. “It wasn’t until I quit the Day School and went all-in in ’93 that things really started happening,” Battle says.

Today, the fruits of his labors, along with those of his assistant of 19 years, Franklin Paucar, can be found throughout the East End, including public restoration projects such as Sag Harbor’s Civil War monument, the once rusted and decayed Mashashimuet Park arch and, most recently (with Chris Denon of Twin Forks Moving), Sag Harbor Cinema’s iconic neon sign, which was destroyed in the devastating 2016 fire and, thanks in part to Battle’s work, relit over Memorial Day weekend.

Battle never really advertised. He grew his business, picking up repairs, antique restoration, fabricating, forging and much more, through good quality workmanship and word of mouth. “I tried to hold to a high standard,” he says, pointing out that he’s never cut corners and always stays focused on the details. “You build name recognition,” Battle adds, noting that he enjoys his work and the problem solving that constantly challenges him and forces him to remain on his toes. “I’ve had an amazing 34 years,” he says.

With so much success behind him, moving back to sculpture is a new adventure, but Battle stands ready to face it. “I started as a sculptor and moved to craftsmanship to make a living and raise my kids. Now I’m coming back to it,” he explains. “My art needed craft,” Battle continues. “Now I’m sort of barreling into the crosshairs, saying, ‘OK, John, it’s time to put the craft back into your art.'”