If you are craving a taste of history on your trip to the Hamptons this summer, there is no better place to stop than the Nathaniel Rogers House in Bridgehampton, now open to the public after a restoration project nearly 20 years in the making.

The 19th-century building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and a landmark in Southampton Town, is one of the few full portico, or temple front, Greek Revival houses to survive across the island.

“It is incredibly meaningful to have a historic home that is a place that welcomes the entire community,” says Nina Rayburn Dec, the director of the Bridgehampton Museum, stewards of the project since the Town of Southampton acquired the house using Community Preservation Fund money in 2003. “It connects the past to the present and the present to the future. It allows everybody to have that visual experience all together.”

The stately house with its grand columned front porch and elegant rooftop balustrades sits on the southeast corner of Montauk Highway and Ocean Road. Over the past 15 years, it underwent an elaborate project to restore it to its former glory.

“It was a labor of love,” says Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman. “It was painstaking historic restoration — it actually won a New York State award for historic restoration. They really went into great detail in terms of historical accuracy and materials and design. It took years to get to this point, but it is now open to the public. We certainly hope that the public takes advantage of it and goes there to learn about local history.”

The Bridgehampton Museum opened the doors to the Nathaniel Rogers House in mid-June, with the first exhibition that showcases the history of not only this important house, but the community.

Dec explains how the home symbolizes the importance of understanding history to move forward in the present. “The Nathaniel Rogers House honors who we’ve been, who we are, and where we are going,” she says.

The exhibit, titled The Rogers House: A Contextual History, features work from Bridgehampton High School students, art by local artists such as Claus Hoie, a racing film to honor Bridgehampton’s racing history and a display of artifacts from the Bridgehampton Fire Department, as well as a few pieces on loan from their archive. While it may seem like the backdrop for these vignettes of Bridgehampton life, the restored spaces are really center stage.

Upon entering the home, visitors can see the timeline of the house pasted onto the foyer walls. Dec says that the current exhibition is “the story we know,” focusing mainly on the previous owners and hamlet’s history.

Not much is known about the roles of women, enslaved individuals, people of color, indigenous people, or migrants and immigrants, Dec explains, but promises that this current exhibit is just the beginning of a larger conversation about those behind the creation of this landmark.

The original house, a small post and beam structure with two main rooms on each of the two floors, was said to be built by Abraham Topping Rose, a county judge, in 1824, though portions of the house have been discovered to date to the 1790s.

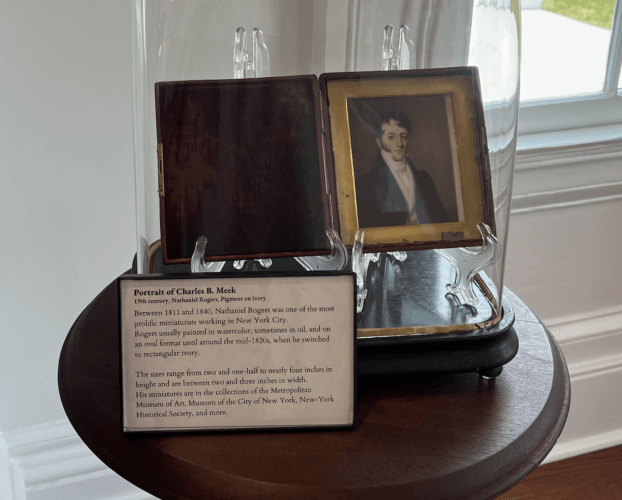

Nathaniel Rogers, a miniature portraitist, purchased the home from Rose, a friend from elementary school, in 1840. In turn, Rose built a larger residence across the street on the northwest corner. Later called Bull’s Head Inn, the building was restored and renovated about a decade ago, becoming home to the hotel and restaurant called Topping Rose House.

Rogers, born and raised in Bridgehampton, was the eldest son of a farmer and his mother was the daughter of a local minister. Though he apprenticed with a shipbuilder, a severe leg injury sidelined him and he took up painting and drawing during his recovery. He eventually became one of the most successful and prominent artists in miniature painting in the 1800s. He co-founded the National Academy of Design in New York in 1826. Rogers’ works are now in the collections of many well-known museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of the City of New York, the New York Historical Society and Yale University.

Rogers expanded the home in the Greek Revival style, adding the impressive front portico with four massive Ionic columns and changing the roofline.

“There are many different reasons why the house embodies a sense of place for Bridgehampton, and therefore the Town of Southampton,” says Julie Greene, the town historian. “Rogers came back to the community where he was from and gave back to this community with this house. By restoring this community center, people can be educated on the history of the town, plus the history of what Rogers did, and his work. It’s just been an absolutely beautiful process.”

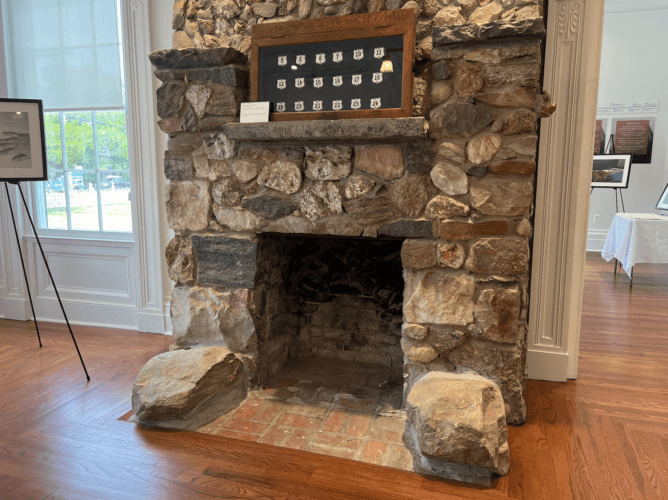

The interior still features the now restored, squatter, federal-style ceilings, vintage window panes, hardwood floors and wall detailing. All of the fireplaces are marble, and one is Adirondack style. Rogers added four parlor rooms, widened the hallways and stairways, constructed more bedrooms on the second floor for his six children and built a third floor, which has additional bedrooms.

Rogers also added a tall decorative cupola, complete with intricate pineapple finials on all four corners. Dec says it has long been a myth that the cupola blew off in the Hurricane of 1938, but rather that it was removed in the 1940s after a persistent roof leak. A historically accurate replica, finials and all, was hoisted atop the house in 2020, on the northern side of the building.

Since it was Rogers who made substantial architectural changes to the home, and was heavily involved in the community, the restored house is named in his honor, explains Dec.

However, he was not the last owner. Rogers died of tuberculosis in 1844. His wife, Caroline Matilda Denison, lived there for several more years, before selling it to the Hunting family in 1857. James Hunting, a whaler, lived in the house from until around 1873 when Augustus and Mary DeBost bought the house. According to Greene, Augustus’ grandfather was Presbyterian minister Schuyler Bogart who served in Southampton. His family would visit in the summers when he was a child and the family was among those known for establishing the Summer Colony in Southampton.

The next owner, local entrepreneur Miles B. Carpenter, turned it into a boarding house, calling it The Hampton House.

In 1894, after the house sat vacant for five years, John N. Hedges, captain of the Mecox Life-Saving Station, and his son-in-law Frank E. Hopping bought the house for $5,730. They undertook some renovations, adding a summer dining room and butler’s pantry on the original structure and expanding the house on the southern wing, as well as closing the porch and reopening the Hampton House, a sort of luxury hotel for the early tourists of the day.

When the hotel closed in 1949, the Hopping family took up residence, living there until 2003, when Southampton Town purchased the residence.

By that time, the building had become dilapidated and was at risk for demolition. The columns were held up by bracing, windows were broken and paint was peeling.

A group of local men soon recognized the house’s historical value, and, wanting to preserve the property, they approached the town with their requests. The town purchased the 7,600-square-foot building in 2003 for $3.5 million. The Bridgehampton Museum entered into a long-term agreement with the town to be its steward.

The multi-phase renovation process was meticulous, taking down walls and replacing floors, Dec says, adding that she feels, “This process was a fantastic example of what can happen when local municipalities partner with nonprofit organizations to do something beautiful for the community.”

Charlie and Kathleen Marder of Marders Nursery in Bridgehampton donated a substantial amount of trees and plantings for the landscaping. The lawn is rich with clover and chewing fescue, plants that reintroduce nitrogen into the soil and require less mowing. All that are missing are the farm animals Rogers once kept.

In 2020, a replica of the home’s iconic white picket fence was erected and surrounds the residence, while wooden shutters adorn the windows and the cupola was raised.

The total cost of the project, excluding the landscaping and the replica of the cupola and picket fence, is estimated to have cost around $11 million.

Though it is a substantial sum, Schneiderman points to the value of commercial real estate. The former Elie Tahari building on the corner of Main Street and Newtown Lane in East Hampton sold earlier this summer for $22 million and now is home to Louis Vuitton.

“It doesn’t compare to this and sold for twice as much,” Schneiderman says “Overall, it’s probably a great investment,” adding it didn’t impact property taxes since the expense came from the Community Preservation Fund and it is a shared asset.

Plus, he points out it helped improve a major, once blighted four corners in Bridgehampton. “Rather than having a mini-mall there, you’ve got a museum property. That’s a great intersection now between Topping Rose and Almond [restaurant] and the NYU Langone building, which is not a historic building, but it was designed to sort of fit in with that traditional architecture.” The building, now home to the medical office, replaced a small shack that many remember as the beer distributor.

“It’s a great little corner of the world there,” the supervisor says.

Inside, the current exhibition, up through the summer, is an eclectic blend of preserved historical artifacts and modern art and culture, encapsulating the contributions of the original homeowners combined with the numerous people who have donated and helped with the restoration process.

The exhibit currently includes numerous photographs by Bridgehampton High School students on display. The racing expo features a large television playing a 15-minute film on Bridgehampton’s iconic racing history, accompanied by a seating area and vintage photographs and posters on display.

The last aspect of the show, “Tell Me Your Story,” encourages museum-goers to fill out small cards with prompts to tack onto a board for all to read. Dec explains that this interactive element allows for an open space for everyone to share their stories from Bridgehampton.

“History is a living, breathing continuum, and by sharing our stories, we are all responsible for each other in some way and become a part of each other’s narratives.”

“A historic place like the Nathaniel Rogers House is a representation of this responsibility, and a place for discourse,” Dec says, “where people can come together and connect. In this time especially we need that more than anything else.”

This article appeared in the July Fourth 2023 issue. Read the full digital version of the magazine, click here. For more articles from our various magazines, click here.

Editor’s Note: Taylor K. Vecsey was among the Community Stars the Bridgehampton Museum recently honored at the Nathaniel Rogers House.