With all that’s gone wrong in the world, 2022 is turning out to be quite a year for architect, historian and author Gary Lawrance. Known professionally as the go-to guy for creating masterful and perfectly scaled physical and digital 3D architectural models, as well as for his bestselling book Houses of the Hamptons, 1880–1930 (co-written with Anne Surchin), Lawrance is mostly getting attention now for his expertise and online proliferation of information about the so-called Gilded Age.

With an extensive background in the history of Gilded Age architecture, landscapes and society, Lawrance has for years been a respected authority when it comes to this fascinating period of great industrial growth and prosperity following the Civil War. The Gilded Age lasted from about 1870 to 1900 — though Lawrance’s focus stretches through 1930. His related blogs and social media have built a combined following of some 500,000 people — his popular @mansionsofthegildedage Instagram account has more than 100,000 followers alone — and his talks and symposiums, both online and in-person, have drawn large crowds from all over the world.

The public interest and his online follower count continue to grow, now faster than ever, as more people watch Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes’ new HBO series, The Gilded Age. The show — starring Christine Baranski, Montauk’s Cynthia Nixon, Carrie Coon, Louisa Jacobson, Denée Benton and other top acting talent — mixes real history with a fictional dramatic thread, while doing its best to capture the look, feel and attitudes of the era.

“The Gilded Age was originally named by Mark Twain. He was kind of making a pun of it,” Lawrance says, explaining that Twain, who wrote the 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today with Charles Dudley Warner, was offering a metaphor about covering otherwise unexceptional materials with a layer of gold, the “artificiality of people pretending to put on airs and gild things to seem better.” Most scholars agree the incisive author of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was also speaking to corruption of the day, hidden just beneath a glimmering gold veneer.

“Gold was always a symbol of wealth, and in the Gilded Age they had just so much money. There was no income tax, they had $100 million to $200 million, which today is not much, but in those days certainly would be billions, with no taxes,” Lawrance says. “Nobody paid taxes — poor people, middle class, nobody, but somehow the country managed. They just had all this money coming in faster than they could possibly spend it.”

As part of Lawrance’s study of the period, he turned his focus to the great homes of the Hamptons elite in his first book, but his research eventually took him south, following the siren song of Palm Beach’s historic wealth and society for what he hoped would be a second book, Houses of Palm Beach, 1900–1950. That book has not yet come to fruition, but throughout the last decade of work, Lawrance has built an encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s most important figures and their stately homes — many of which have long since been razed to make way for more modern structures.

Palm Beach really got going after the Gilded Age was officially over, though some say the era never really ended in this exclusive community. “The Hamptons was always considered like a second Newport (the first wealthy resort) … and after about World War I, the Hamptons rises to become the very chic place, where it’s really dubbed the American Riviera,” Lawrance continues. “That’s when Palm Beach also starts to rise because it becomes a winter resort, because travel is easier, people are taking more trains, people are taking more boats. … The reason I was going to do the Palm Beach book was because Palm Beach and the Hamptons are pretty much summer and winter. It’s the same people building the same houses, the same social world.”

Lawrance points out that Palm Beach and West Palm Beach were founded by industrialist Henry Flagler, of Standard Oil, who made his way south in 1890 and completed the breathtaking, 1,100-room Royal Poinciana Hotel, Palm Beach Inn (now The Breakers) and his landmark Whitehall mansion by 1902. “Flagler extended the railroad and he brought it down to Palm Beach, which was mostly just swamp and alligators and untamed land,” Lawrance says, noting that the railroad made it possible for more people to comfortably make the journey. “He sort of set it as the place to be.”

Then, he explains, “It explodes as a major resort, and the houses get huge and monstrous, and it becomes a playground for the very rich.” And with the well-heeled residents came a series of grand mansions. Sadly, many of the most famous homes did not survive as times changed in the post-World War II era. For most, their legacy remains only through photographs and stories, which Lawrance shares here.

Whitehall, 1902 – Palm Beach

Remains as a museum

One of the first Palm Beach mansions that equaled those that could be found in Newport and other Gilded Age locations, Henry Flagler’s 55-room, white-stucco-columned edifice was also one of the largest in the first days of Palm Beach’s transition from wood cottages to palatial grandeur. Designed by the noted architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings, Whitehall served as a hotel for many years before it was restored to its former self. It is now open to the public as a museum.

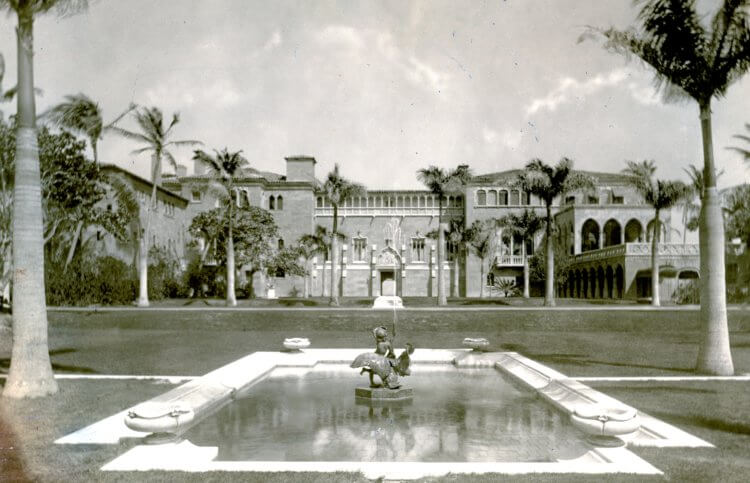

El Mirasol, 1919 – Palm Beach

Demolished in 1959

El Mirasol, “The Sunflower,” was built for Edward T. Stotesbury and his wife Eva Stotesbury by star Palm Beach architect Addison Mizner. The 42-acre estate was entered off North County Road, which ran through the entire property. The eastern part was for the residence on the ocean and across the road to the west for gardens and pavilions. Another sprawling fantasy villa, it was always being expanded according to the Stotesburys’ whims. It also was the scene of magical parties and galas. The Stotesburys had El Mirasol as their winter residence, as well as a palace-scale mansion outside of Philadelphia and another monumental summer house at Bar Harbor, Maine. Unfortunately, all three architectural treasures have been demolished, but El Mirasol’s arch still stands.

Casa Bendita, 1921 – Palm Beach

Demolished in 1961

Among Mizner’s masterpieces, this sprawling and colonnaded winter dwelling of steel titan John S. Phipps was one of Palm Beach’s largest homes. On North County Road, Casa Bendita, meaning “Blessed House,” had two swimming pools and a tower that faced the Atlantic Ocean. The loss of this house in 1961 was a sad moment in Palm Beach architectural history. The gazebo remained for many years until it, too, was reduced to rubble in 2011.

Casa Florencia, 1922 – Palm Beach

Demolished in 1952

Built by Mizner in 1922 for Dr. Preston Pope Satterwhite and his wife Florence (the home’s namesake), Casa Florencia was set on the water at South Ocean Boulevard. Florence, who was the extremely wealthy widow of James Martin, married Dr. Satterwhite in 1908 and continued with a life of entertaining, along with collecting art, antiques and jewels. The home was furnished with many fine European antiques from the couple’s travels, but Florence only got to enjoy it for a few short years. After she died in 1927, Dr. Satterwhite sold the house. It was demolished in 1952 after being deemed outdated and too expensive to maintain.

Playa Riente, 1923 – Palm Beach

Demolished in 1957

Another Mizner home, Playa Riente, which means “Laughing Beach,” was originally built for oil millionaire Joshua S. Cosden in 1923 on North Ocean Boulevard. Then in 1926, Anna Dodge and her husband Hugh Dillman bought the already large house and expanded it, creating an even more spectacular oceanfront home. Anna Dodge, who was the widow of Horace Dodge (of the fabulously wealthy automobile family), hosted elaborate parties and entertainment there, making her one of the queens of Palm Beach society. As the years passed, Anna had little use for Playa Riente. She tried to sell it in the 1950s, but no one wanted it as a private home, and the town of Palm Beach didn’t want it to be used for anything but a private dwelling. She then held a huge auction of the contents and demolished this former epicenter of Palm Beach society. The property has since been subdivided for new grand homes, but nothing like the lost Playa Riente.

Cielito Lindo, 1927 – Palm Beach

Split in two, but still standing

With a name loosely translating to “A Piece of Heaven,” this magnificent, 45,000-square-foot Mediterranean home, designed by Marion Sims Wyeth, was a perfect getaway for owner and Woolworth five-and-dime heiress Jessie Woolworth Donahue and her husband James Donahue. The famously rich owner of Wooldon Manor in Southampton was rejected by the Hamptons elite for having too much money, but Palm Beach society gladly embraced Donahue and her tremendous fortune. She sold the house in 1948, after her husband’s suicide, and Cielito Lindo was later split in two in order to accommodate Kings Road, where it remains today.

Mar-a-Lago, 1927 – Palm Beach

Still standing as a private club

In a land of extra-extravagant mansions, the dreamlike, 62,500-square-foot, 126-room Xanadu creation designed by Wyeth for Marjorie Merriweather Post tops all others with the most rooms, the tallest towers, highest price tag and the best location. If one were designing a mansion that was half home and half stage set, Mar-a-Lago (Spanish for sea-to-lake) fits the bill. As heir to her family’s cereal fortune, Post was one of the richest women in the world at the time and filled her homes with the rarest antiques and treasures. And her entertainments were not to be missed, no matter what else was going on. If Hollywood had to create the ultimate Palm Beach mansion, it would be hard to top Mar-a-Lago — which of course is now owned, and made even more prominent (and infamous) by former President Donald Trump. Gilded interiors, beautifully colored tiles and mosaics, chandeliers, and silver and gold services at the tables — Marjorie wins the prize.

Find more about Gary Lawrance and his work, and links to his various Gilded Age-related accounts, at garylawrance.com.